Applications

Playing chess with GPT:

a guardrailed example

Language models are fundamentally stochastic next-token-predictors: autoregressive models that generate text based on existing text one token at a time. Unsurprisingly, they are not great chess players.

And yet... they are not terrible chess players either. Despite sensationalist media reports to the contrary, an advanced model like GPT-5 can play chess reasonably well, at the level of an unsophisticated amateur: It knows the rules, it can even offer a coherent narrative, but it will make stupid mistakes, even sacrificing its queen or getting itself into an unavoidable checkmate.

So why the terrible reputation? Why the sensationalist coverage? The reason is simple: the ability to play chess is not the same as the ability to reconstruct the state of a chessboard based on a long list of prior moves. Yet when we naively "play chess" with a language model, offering moves and expecting moves in return, at every conversational turn we expect the language model to reconstruct the entire state of the board from scratch, from an ever longer conversation containing an ever increasing number of moves and countermoves. It should come as no surprise that ultimately, the model fails miserably.

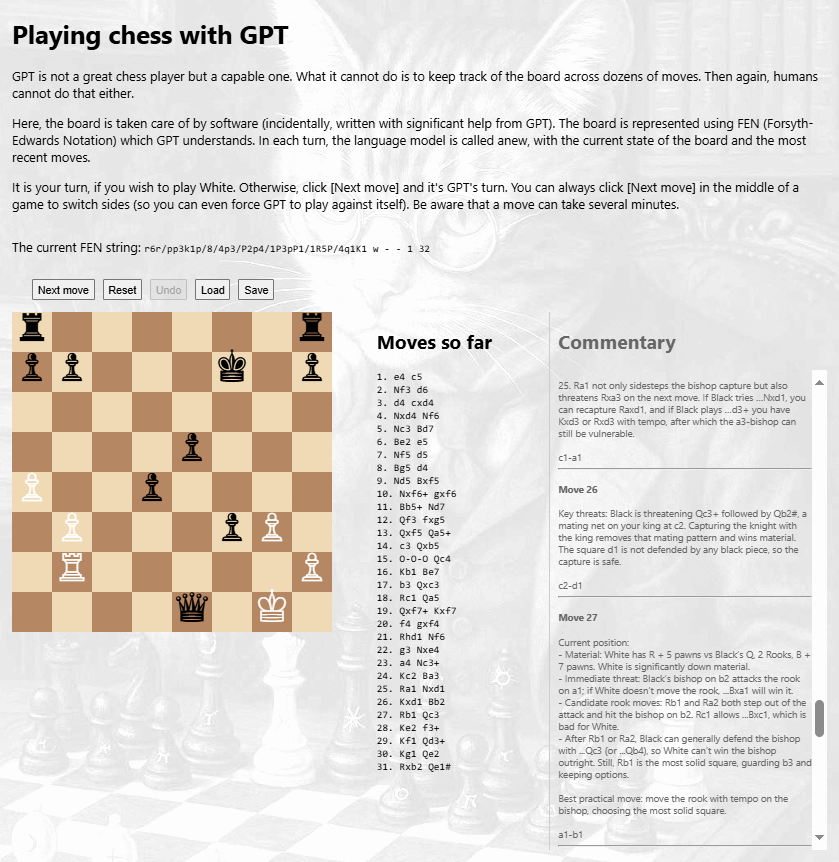

Yet it is quite possible to get a language model to play well. But this requires external scaffolding: software code that keeps track of the chessboard state, prompts the model for the next move, rejects invalid moves, and updates the board.